When a Gay Friendship Ends, the Grief Is Bigger Than the Friendship

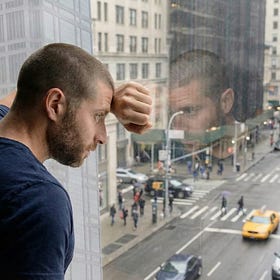

For a lot of us, close friends weren’t supplemental. They were structural. The loss knows the difference even when we don’t.

You didn’t hear about the divorce from him.

You heard about it at a party, six weeks after it happened, from someone who assumed you already knew. And you stood there with a drink in your hand doing the math.

The diagnosis, three years ago, where he was the first person you called. Before your partner, before your family. The time he sat outside the hospital waiting room for four hours because you asked him to and he just did. The fights you’d had, the things you’d said out loud to him that you haven’t said to anyone else since.

Six weeks. A party. Someone else’s mouth.

You drove home doing that specific kind of arithmetic where you keep getting the same answer but keep checking the sum because the answer doesn’t make sense.

You thought you were load-bearing. You were not.

The friendship is over. You’re not sure he knows it’s over.

That bewilderment, the gap between what you thought the friendship was and what it turned out to be under actual pressure, is where this piece begins.

What the Exile Response Actually Is

The grief that follows a gay friendship ending often feels wrong in scale. Too large. Too persistent. Too disorienting for something culture keeps calling “just a friendship.”

Here’s what I think is actually happening.

For a significant number of gay men, close friendship isn’t an addition to an already intact support network. It is the network. The thing that filled the space where family of origin was conditional, or absent, or only available for the approved version of you.

The person who was there for the coming out, the bad relationship, the grief your family didn’t understand, and your colleagues couldn’t know about. The one who held the real version of you before you were certain it was safe to have one.

That is a different category of relationship than “close friend” implies.

When that person exits, the nervous system doesn’t file it under social loss. It files it under exile. And exile is not a dramatic word. It’s the accurate one.

It describes what your system already catalogued, once or more than once, before this friendship existed. The conditional welcome from family. The years of editing yourself in rooms that would have punished the unedited version. The particular exhaustion of being let in partially but never fully.

The new loss arrives and the old ones move through it. Your system doesn’t sort cleanly between the sixteen-year-old who learned he wasn’t safe to be known, and the thirty-five-year-old whose best friend didn’t call during the divorce.

This is why the grief is disproportionate to how culture classifies it. It isn’t disproportionate. It’s proportionate to the actual accumulated weight of what that friendship was compensating for.

You’re not overreacting. You’re responding to the real size of what was lost.

Load-Bearing vs. Utility: How to Tell the Difference

Most of us don’t know which kind of friendship we had until something tests it.

Load-bearing friendships have a specific quality. They hold you in the hard version, not just the pleasant one. The friend knew about the thing with your family. The thing you don’t tell people at parties. He didn’t require you to perform fine before you got through the door.

You’ll also recognize them by their absence.

If someone disappears and you feel the gap in your daily scaffolding, not just your social calendar, that was load-bearing. If the loss makes you feel unwitnessed, not just less entertained, load-bearing.

Utility friendships are real. Warm. They genuinely mean something. But they’re built for enjoyment, not emergency.

The actual diagnostic: did this person know something about you that required courage to say out loud? Did they stay when what you said was hard to hear? Did the friendship ask something of both of you, or just provide something?

Those are different foundations.

The confusion most of us carry is that familiarity reads as intimacy. Three years of shared dinners feels like three years of being known. It isn’t, always.

You can know someone’s social geography, their opinions, their ordering habits, their flatmate drama, and still not know their interior. You can be genuinely important to each other and still be each other’s entertainment rather than each other’s structure.

And here’s the part that’s hardest to sit with: the load-bearing can run in one direction.

You can be structural for someone who is supplemental for you, and neither of you knows it until the weight goes on. The asymmetry isn’t malicious. It’s just what happens when two people bring different deficits to a friendship and neither one names it.

Where do you feel this right now? There’s probably a friendship coming to mind. That’s the one.

What Gay Social Culture Produces, Specifically

The pattern isn’t individual. I’ve watched it repeat across enough sessions to know it’s structural.

Gay social scenes, especially city-based ones, are organized around visibility.

The friend who is present, functional, and available for the version of gay life that looks like it’s working gets included. The one who is struggling, who brings the real version of himself, who has needs that require something from the people around him, gets quietly deprioritized.

Not through cruelty. Through a conditioning so old most of us can’t feel it operating.

Queer teenagers who survived hostile environments often did it by learning, with precision, which version of themselves was safe to show and where.

That training doesn’t retire when the environment changes. It moves into adult social life and shapes the friendships you form, the friendships you attract, and the level of depth you unconsciously signal you’re available for.

The friend who doesn’t call usually comes from somewhere that trained him to perform fine under pressure.

Catholic family. Late coming out. A decade of managed presentation before he found gay social life, which then rewarded the same management under different aesthetics.

Calling you, the person who knows the real version of him, would require dropping the performance in the moment he most needs it to hold. So he calls the people who only know the surface. And the surface holds fine.

Gay social culture didn’t create that reflex. But it maintained the conditions where it never had to change.

The Part About Our Own Complicity

It’s a Sunday in November, raining.

You’re at brunch with four people you’ve known for two years. The table is loud. Someone is telling a story about a nightmare date and everyone is laughing and the laughter is real, and you are present for all of it, and also completely alone inside it.

You know these people’s preferences, their opinions, and their ongoing conflicts with their flatmates. You don’t know what any of them are actually afraid of. You’ve never asked. They’ve never offered.

The brunch has been recurring for two years without a single real thing being said.

That’s not their failure. That’s a collective agreement you’re all maintaining.

You manage the depth of your friendships to a level that feels safe, which is usually several floors below actual intimacy.

You keep the conversation at the level of opinion and anecdote because opinion and anecdote don’t require you to be seen, which means they can’t reject what they haven’t encountered.

The substitution of familiarity for depth isn’t an accident. It’s a choice made repeatedly, because depth requires risk, and most of us learned early that risk with other people went badly.

The utility friendship isn’t a lesser version of a real friendship. It’s a rational response to an environment that punished need.

The repair conversation problem is downstream of this.

You don’t avoid it only because vulnerability is uncomfortable. You avoid it because starting one means admitting the friendship mattered enough to be worth the exposure of asking for it back.

Which means admitting you’re someone with friendships that matter that much. Which requires a level of self-disclosure most of us spend decades practicing not to do.

So the friendship thins. You watch it happen. You don’t interrupt it.

And then it’s over, and you’re alone with it. Which is not different from how you were when the friendship was alive.

The Two Conversations

Both require saying something out loud. For most of us, that is the entire obstacle.

If you want to try to repair:

Pick one specific thing. Not a catalogue, not a case file.

“I’ve noticed we’ve been less in touch and I don’t want to let it go without saying something. Something shifted and I don’t fully understand it. Can we talk? Not to build a case. Because I’d rather name it than lose it.”

No historical record. No proof of who reached out more. One question: is this worth one honest conversation?

If the answer is no, or nothing, that’s information too. Painful. But cleaner than the alternative.

If you need to release:

“I’ve been sitting with this for a while. I think we’ve grown in directions that don’t connect the way they used to. I’m not angry. I don’t have a speech. I just think I owe us both more honesty than I’ve been showing up with.”

No magnanimity theatre. No “I hope we can always...” You probably can’t, and both of you know it.

Clean endings are an act of respect.

The slow fade keeps something unresolved, taking up space, returning no warmth. It also keeps you in a story with no ending, which is its own specific damage.

What You Can’t Unknow After

The grief doesn’t last forever. But what it leaves behind is useful, if you let it be.

You now know the difference. Between the weight a load-bearing friendship carries and the weight a utility friendship can manage. You’ve felt both. And you can’t unfeel them.

That knowledge changes what you can accidentally accept going forward. Not because you’ve acquired a new framework. Because something in your body knows the difference now between being held and being entertained, and it won’t mistake one for the other the same way it used to.

The brunch table will still happen. The utility friendships will still exist, and some of them will be genuinely good. But you’ll know what they are. And you’ll know what they’re not.

That’s not resolution.

It’s something more honest than the confusion you walked in with.

Thank you for reading,

Gino

P.S. Who in your life right now holds the actual weight of you? Not as a standard to measure others against. As information about where you are.

If you enjoyed this post, please tap the Like button below. ❤️ It really does help!

Free subscribers keep the conversation alive. Paid subscribers fund the work. Whatever you do, thanks for doing it.

Forward it to one friend who’d actually read it, not just “support” it.

All examples in this piece are composites drawn from patterns observed across therapeutic work with gay men. Details have been altered to protect confidentiality. No single story represents an individual person.

This newsletter is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not replace therapy, diagnose, treat, or prevent any condition.

The Loneliness That Has No Name

Why gay men feel most alone even in crowded rooms. A look at emotional invisibility, minority stress and the quiet cost of being unseen.

Oh boy. There’s so much here.

I’ve literally been going through this exact evaluation in my life, but I didn’t have words for it.

This is just wonderful. So incredibly valuable. Especially the part about how both parties can regard the friendship differently. One thinks it’s loadbearing the other one thinks utility.

For me, I tend to invest. And I used to overdeliver a lot, which makes it really hard to tell the difference between loadbearing and utility. Not anymore. But I’m glad I have words for it now. 😊💕

Life is a journey.

Some people are with you for part of that journey and then go their own way.

That is their journey.

Or your journey goes somewhere they don’t want to go.

That is your journey.

Be grateful for the time you shared.