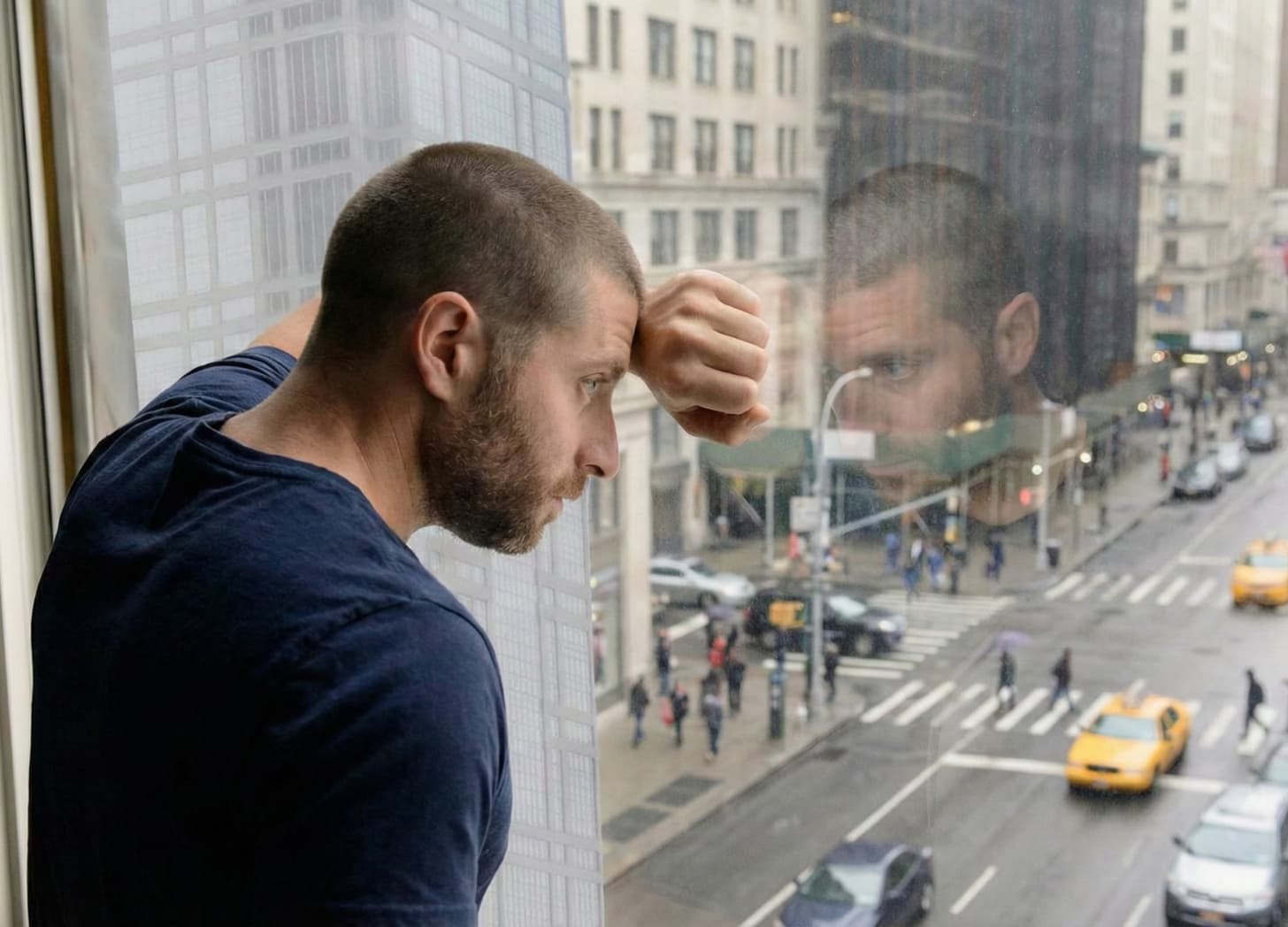

The Loneliness That Has No Name

Why gay men feel most alone when surrounded by people

His phone screen lit up during our session.

Three dating app notifications, two group chats, a Friday drinks invite. He apologized, silenced it, then looked at me with a familiar expression. Not embarrassed about the interruption. Something else. Something harder to name.

“My calendar looks like I have a life. Like I’m doing everything right. Putting myself out there, you know?” He gestured at the phone as if it were evidence in a trial. “But scrolling through profiles of men who look happy, settled, like they’ve found answers...”

He trailed off. Started again. “I show up to things. Stay just long enough to not seem weird. Then sit in my car afterwards because the silence after all that noise feels too sudden.”

He had people, just not those who understood him.

Queer loneliness has a unique flavor that doesn’t show up in most descriptions of social isolation. You can be at Pride, surrounded by thousands of queer people, and feel li…