The Rivalry We Recognize: Why Gay Men Can't Stop Watching Heated Rivalry

What happens when validation exposes what you're avoiding.

Three weeks in, my friend texts at 2 AM: “Started episode one at 11. Finished the season. What the f&%k just happened to me?”

I know exactly what happened to him.

The same thing that’s been happening to hundreds of thousands of gay men since late November, the same thing that made this show Crave’s biggest original debut on record, and the same thing that has people rewatching episodes they watched two days ago.

Not because the show is perfect.

Not because it breaks new ground.

But because it does something much of mainstream queer media rarely does.

It lets desire be complicated without apologizing for it.

And then it forces you to look at what you’re doing with your own.

The Pattern We Don’t Name

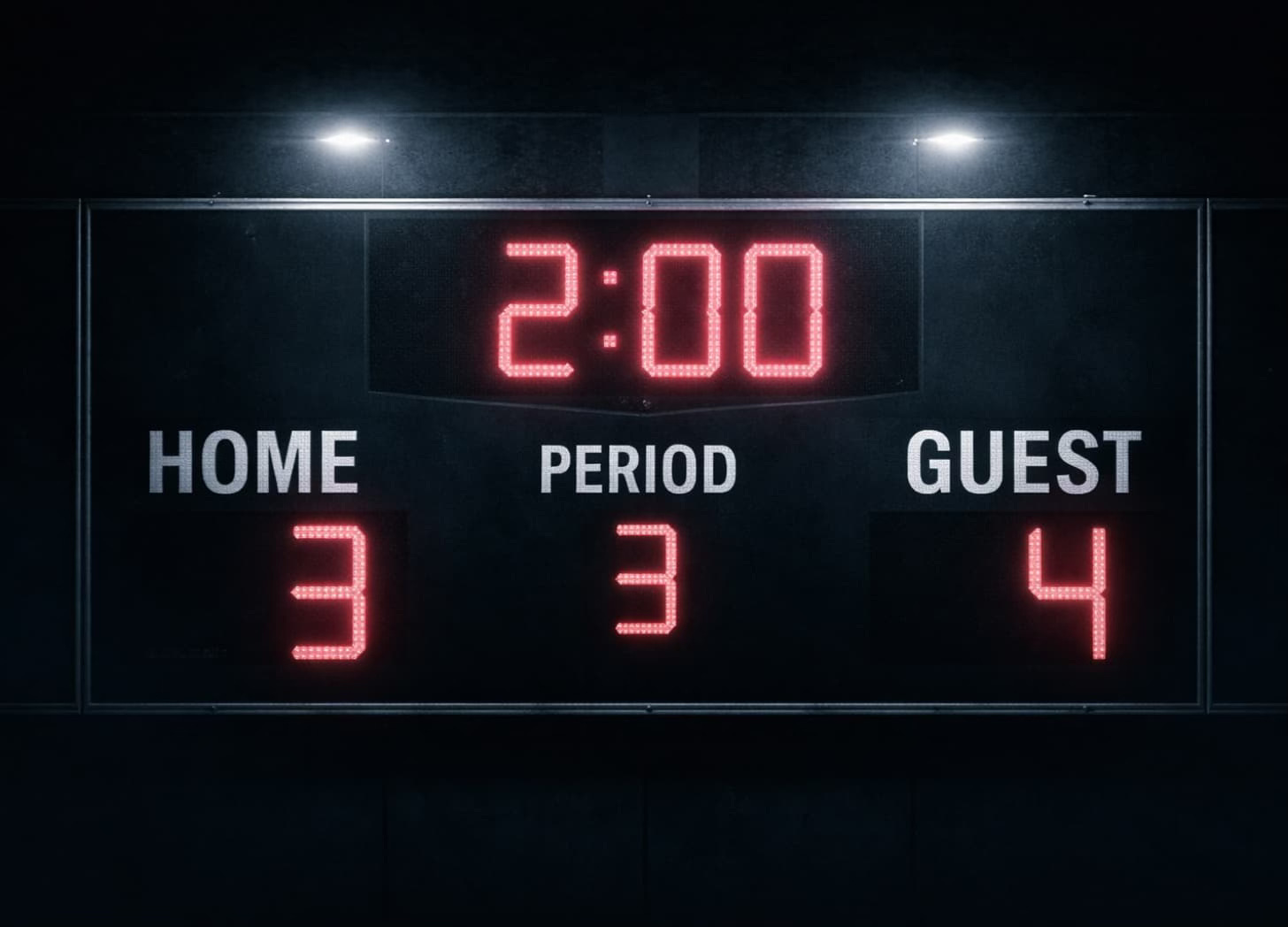

Shane and Ilya hate each other on the ice. Off the ice, they can’t keep their hands off each other.

For years. In secret.

The rivalry doesn’t soften. The sex doesn’t domesticate them.

They keep trying to destroy each other professionally while building something private that has no language, no category, no Instagram aesthetic.

Gay men can’t stop watching.

Not because it’s relatable in the obvious way. Most of us aren’t professional athletes conducting secret affairs.

Because the emotional architecture is so familiar it hurts.

Here’s what the show gets right without trying:

It understands that for many gay men, desire and danger learned to speak the same dialect.

Shane and Ilya’s attraction exists in the most hypermasculine space imaginable.

Professional hockey. A place where queerness historically gets you benched, traded, or quietly pushed out. Where your body is public property, scrutinized and judged. Where vulnerability is weakness and weakness is career death.

So what do you do when you want someone in that environment?

You convert the want into something legible. You make it look like rage. You let aggression be the container because aggression makes sense here.

You can slam someone into the boards, and everyone sees rivalry.

Nobody sees recognition.

One of my clients, I’ll call him Marcus, spent his twenties in finance. High-performing, aggressive, competitive.

“The first guy I ever slept with," he told me once, "was someone I'd been in direct competition with for a promotion. We hated each other. Or I thought we did. Turns out we were just... I don't know. Using acceptable cover.”

That’s the show’s genius.

It depicts desire that can’t announce itself, so it borrows hostility’s costume. The push becomes the pull. The violence becomes intimacy’s only available vocabulary.

For many gay men who grew up learning that wanting another man required translation, camouflage, and some acceptable reason to be in proximity, this pattern doesn’t need explanation.

It just is.

For gay men who grew up in spaces where touch was suspicious unless it was rough, where the only acceptable physical contact between men was competition or combat, the line between violence and intimacy has always been thinner than anyone wanted to admit.

The locker room handshake that lingers. The wrestling match that goes on too long.

You learn to hide what you want inside hurt.

You learn that roughness doesn’t raise questions, but tenderness does.

Heated Rivalry understands this grammar.

Shane and Ilya don’t need to verbalize what their bodies already know. They just keep finding ways to make contact that the sport already authorizes.

Hit me. I’ll hit back. Nobody watching will understand what we actually mean.

There are moments all through the season where you can see the private audience at work.

Not the crowd. Not the coaches. Not the league.

One person.

The glance that lingers half a beat too long. The refusal to fully celebrate because the celebration is not for everyone. The feeling that even the public stuff is, in some strange way, a message.

I see you seeing me. I perform for your eyes. Everything I do publicly has a private audience of one.

How many gay men have lived some version of that? The public performance with the secret recipient. The achievement that’s really a love letter you can’t send. The success that’s actually a mating call disguised as ambition.

One client described his entire athletic career that way.

“I told myself I was competing for scholarships, for my dad’s approval, for my own pride,” he said. “But really? I was performing for this one guy on the team. Every game was for him. He never knew.”

The show doesn’t explain this pattern. It just depicts it.

And in that depiction, something gets witnessed that rarely makes it to screen: the specific choreography of desire that can’t name itself but still insists on existing.

When Recognition Becomes Diagnosis

Here’s where it gets complicated.

The show gives you validation.

For six episodes, the camera treats your specific emotional architecture like it makes perfect sense. The rivalry that was really intimacy. The aggression that was really want. The performance with a secret audience.

You don’t have to explain it. The show already knows.

That validation does something.

It loosens something in your chest you didn’t realize was locked.

But then it charges a fee.

What people keep telling me isn’t what I expected.

They’re not talking about the sex scenes, though the show’s marketed on them heavily. They’re talking about the late-season shift, when the intimacy starts showing up in normal, almost boring places.

An airport pickup that turns into a car ride where a hand gets held, openly, like it’s the most natural thing in the world.

A quiet domestic beat where groceries exist and no one is posturing, because there’s nowhere to perform. Just two men alone with the reality of what they are to each other.

One person told me:

“I’ve watched plenty of gay sex scenes. This is the first time I’ve seen two men hold hands and felt like I’d been punched in the throat.”

The revolutionary moment isn’t the bedroom. It’s being chosen out loud.

Being claimed where it counts. The moment someone treats you like you matter in spaces that historically required you to disappear.

For men who spent years making themselves smaller in public, that’s what cracks them open. Not the explicit content. The ordinary intimacy that was historically invisible.

The show’s been out for eight weeks. People are rewatching it like it contains some secret they missed.

But I don’t think we’re looking for secrets.

I think we’re looking for more time inside that recognition before we have to face what it reveals.

Permission doesn’t just validate where you’ve been. It exposes where you still are.

One person described it perfectly:

“The show made me realize I’m living like Shane in season one. Still hiding. Still pretending the relationship that matters most is casual. And now I can’t unsee it.”

That’s the show functioning as a diagnostic tool.

The moment you recognize the pattern on screen, you can’t pretend you’re not still living it. The validation becomes a mirror. And mirrors don’t lie about the gap between what you watch and what you’re allowing yourself to have.

For men who came out later, who built their relational maps in private and with caution, who missed the developmental windows where most people learn relationship basics, this hits with a particular grief.

Not just “I recognize this.”

But “This is what I didn’t get.”

A client in his late forties watched the show and didn’t speak for the first ten minutes of our session. Finally:

“I’m watching these two kids figure out how to want each other, and I’m just... I didn’t get that. I got married to a woman instead. And by the time I came out at 44, I’d missed the entire tutorial.”

The show becomes a mirror for the missing blueprint.

The skills you had to teach yourself in your thirties that most people absorbed at sixteen. The ordinary milestones that felt revolutionary because nobody prepared you for them.

This is the bittersweet edge of representation.

Relief that someone finally depicted your emotional architecture. Grief that it took this long. Pressure that now you know better, you have to do better.

The rewatching isn’t just comfort.

Sometimes it’s confrontation.

The show keeps asking the same question: if these two can build something real inside a space designed to destroy it, what’s your excuse?

Permission or Hiding Place?

But here’s where the show gets slippery.

It also offers permission to stay exactly where you are.

Most queer media follows a redemption arc. Come out. Process the internalized homophobia. Make the relationship public and therefore real.

The ending is always integration, acceptance, wholeness.

Heated Rivalry plays with that structure, then complicates it.

It gives you tenderness without making it tidy. It gives you love without pretending love fixes the environment it has to live inside.

So when you’re watching and feeling validated, you have to ask: Is this permission to build intimacy on your own terms? Or permission to avoid the risk of wanting more?

A client’s been seeing the same guy for three years. Not officially. Twice a month, they meet up.

“Everyone tells me I should define it,” he said. “But why? This works.”

Maybe it does work. Maybe his complication is genuine choice, not leftover survival strategy.

But maybe the show’s helping him avoid finding out.

The show can’t answer that for you. It just holds up the mirror and asks: which one is this?

What the Season Finale Doesn’t Do

The season ends with something many queer stories still refuse to give: a real emotional turn that doesn’t rely on tragedy.

Most of the finale is quiet. A cottage. No audience. No locker-room performance. Just two men finally having enough uninterrupted space to feel what they feel.

And then the real world breaks in.

Not with a neat, cinematic “and now we’re public” bow.

With the messy reality of being seen before you’re ready, and having to say something anyway.

The show does not end with a grand public kiss at center ice. It does not turn their relationship into a PR campaign.

But it also doesn’t pretend secrecy is the only possible ending.

It lands in that uncomfortable middle ground most gay men know too well: the part where love becomes undeniable, but the logistics and timing and fear have not magically evaporated.

For gay men watching, that’s either the most radical permission or the most devastating mirror.

Maybe both.

Not the ending where everything gets resolved.

The ending where the wanting is finally spoken plainly, and you still have to live with what that changes.

The show doesn’t tell you what to do with that. That’s your work to figure out.

The Cost of Seeing Clearly

The show’s success isn’t about the hockey. It’s not about the sex scenes.

It’s about finally seeing a specific psychological pattern that countless gay men have lived through but rarely saw depicted: wanting someone in a space designed to punish wanting, and finding ways to want them anyway.

Not by fixing yourself. Not by coming out into acceptance.

But by building something real in the margins, and then having to decide whether the margins are where you belong, or where you learned to survive.

Until you have to ask:

Is the contradiction still protecting me, or just keeping me small?

The show’s been renewed for season two, and the creators have said they’ll draw from the next book about Shane and Ilya.

And somewhere, right now, another gay man is starting episode one at midnight, about to text his friend twelve hours later asking what the f&%k just happened to him.

What happened is he got seen.

And now he has to decide what to do about it.

Until next week,

Gino x

P.S. Where does rivalry still cover desire in your life? And is it the cover you still need, or the cover you’re just used to?

If you enjoyed this post, please tap the Like button below ❤️ Thank you!

All examples in this piece are composites drawn from patterns observed across therapeutic work with gay men. Details have been altered to protect confidentiality. No single story represents an individual person.

This newsletter is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not replace therapy, diagnose, treat, or prevent any condition.

Thank you for this astute analysis of HR. I've watched it twice and will undoubtedly watch again. I also bought the books. I can't get enough of them and their story. I wonder what your thoughts are re: why this series has become a favorite for many straight people as well. The acclaim, beyond the queer community, is phenomenal. Thanks again!

There is this line I read in Psycho-Cybernetics a little while ago and I fell in love with it. It goes like:

"A man can't feel affection if he doesn't have an outlet for aggression."

But I didn't realize how one could morph into the other in places where the other is impossible to exist.

Great read, G.