Why Gay Men Treat Friendships Like Ongoing Auditions

The attachment wound you’re not naming is the one happening with the people who are supposed to know you.

He sends me a voice note at 2:47 AM. Not drunk. Just awake in that specific way where the performance finally cracks.

“I don’t think any of my friends have seen me cry. Like, actually cry. Not the cute kind where your eyes get a little wet at a movie. The ugly kind where snot happens and you can’t talk.”

Pause.

“I don’t even know if they’d want to.”

The thing lodged in my throat listening to this? I knew exactly what my friend meant.

The Math No One’s Doing

Straight men don’t calculate whether their buddy wants to f%ck them every time they get a compliment on their haircut. Gay men do that math constantly. Is this care or is this cruising? Is he my friend or is this a slow-motion rejection? Am I reading affection wrong again?

The sex variable ruins everything. Not because sex is bad. But because the possibility of it contaminating every gesture means you can never fully land in safety.

You hug him goodbye after dinner and your nervous system runs three separate threat assessments: Did I hold on too long? Not long enough? Is he reading this as interested? As desperate?

Attachment theory has a name for this: anxious-avoidant patterns. The child learned early on that reaching for connection may lead to rejection, so they develop complex strategies to test for safety before allowing themselves to be vulnerable.

Except now the child is thirty-six and doing the same thing at Sunday brunch.

The research on gay male friendships is sparse, buried under studies about dating apps and coming out narratives. But what exists is damning.

Gay men report fewer close friendships than straight men or lesbians. Lower trust. Less emotional support. Higher rates of social isolation even when surrounded by other queer people.

We built community on shared trauma instead of shared healing. Then wonder why it cuts.

When Your Friends Ghost and No One Calls It That

A client described his friend group imploding over eighteen months. Not one fight. Not one conversation. Just people gradually responding slower to texts, making excuses about being busy, removing him from plans without explanation.

He kept wondering what he’d done wrong.

“With a breakup, you at least get closure. Your friends just... evaporate.”

Romantic relationships end with conversations. Friendships end with read receipts and radio silence. You’re left scanning months of interactions for the moment you became disposable. Was it something you said? Something you didn’t say? Did you get too vulnerable? Not vulnerable enough?

The cruelty is that gay friendships operate under invisible hierarchies nobody admits exist. Who gets priority when someone couples up? What happens to the single friend who doesn’t fit the dinner party vibe anymore? The ranking system is often based on attractiveness, income, relationship status.

High school never ended. It just moved to Instagram and learned better vocabulary.

A friend told me once, “I realized I was the designated single friend. Like, my role in the group was to be slightly messy so everyone else felt more stable.” He laughed when he said it. The laugh where your ribs hurt after.

The Performance Cage

You can’t have an ugly day. Can’t show up messy. Every hangout is partially an audition to stay relevant. One wrong move and you’re the dramatic one. The needy one. The one people tolerate but don’t actually want.

Anxious attachment in friendships looks like:

Needing constant reassurance you’re still in the group

Over-texting, over-planning, trying to lock in plans weeks ahead because if you don’t initiate, nobody will

Interpreting any distance as rejection

Reading every group chat for subtext about your standing

Being the one who always organizes, always remembers birthdays, always shows up, convinced that stopping would mean permanent erasure

Avoidant attachment looks like:

Disappearing the second things get emotionally real

Keeping thirty acquaintances, zero people who actually know you

Using humor as body armor against intimacy

Pulling away when someone wants more depth

The friend who’s “busy” until the hot new guy joins the group

And here’s the pattern therapy rooms are full of: anxiously attached gay men pursuing avoidant friends, trying to earn the emotional availability that never arrives. Recreating the childhood dynamic where love meant begging to be seen.

Straight culture told us we were too much. Gay culture tells us we’re still not enough.

Different judges. Same verdict.

What Attachment Theory Missed About Us

The research on attachment styles comes from studying straight, white, middle-class children and their mothers. Useful framework. Incomplete picture.

Here’s what it didn’t account for: What happens when your first attachment figures reject your actual self? When safety required hiding the core of who you were?

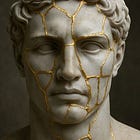

We learned early that showing up whole risked annihilation. So we edited. Performed. Found the version that was acceptable.

Now we’re doing the same thing with chosen family, except this time we’re the ones policing it.

Gay men developed attachment adaptations that psychology textbooks don’t name. The hypervigilance that scans every room for threat. The code-switching that happens so fast you don’t notice you’re doing it. The performance of unbothered coolness while your stomach acid rewrites your esophagus.

These aren’t character flaws. They’re survival architecture. The problem is when survival mode becomes the only mode. When you can’t remember how to be soft because softness meant target practice.

In my online therapy practice, I see the same wound wearing different clothes. The man who has a hundred Instagram friends but nobody to call when his father dies. The one whose group chat is active daily, but he’s never mentioned that he’s thinking about quitting his job. The guy who throws the best parties and goes home alone to panic attacks nobody knows about.

They all say the same thing, different words: “I don’t know if my friends actually like me, or if they just like what I do for them.”

That sentence? That’s attachment trauma speaking through queer experience.

The Attachment Patterns We’re Repeating

Watch what happens when someone in a gay friend group actually needs something. Not advice. Not a place to vent. Real need. Emotional mess. The kind of vulnerability that doesn’t come with an Instagram-ready resolution.

See how fast people scatter.

Emotional availability gets coded as weakness in many gay male cultures. We learned to survive by being sharp, defended, funny. The friend who shows up needy becomes the friend people avoid. Anxious attachment reads as too sensitive. Avoidant attachment reads as aspirational.

The culture rewards the latter. Punishes the former. Then wonders why everyone’s lonely.

I had a client whose best friend of eight years stopped talking to him after he had a breakdown. No warning. No conversation. Just vanished. When he finally got an explanation months later, the friend said, “You were bringing too much heavy energy. I needed to protect my peace.”

Protection is necessary. But when our peace requires other people’s silence about pain, we’re not building community. We’re building isolation with better PR.

What Research Says About Hope

Here’s what attachment theory gets right that’s worth holding onto: patterns aren’t permanent.

Secure attachment can be earned in adulthood. It’s called earned security, the research term for “your childhood f&cked you up, but you can heal anyway.”

Studies on attachment flexibility show that people can shift from anxious or avoidant patterns toward security through consistent, safe relationships over time. Through therapy. Through the hard work of learning that vulnerability won’t destroy you when shared with people who’ve proven they can hold it.

The keyword: proven. Not hoped. Not assumed. Proven through repeated small acts over time.

This is why the friend who shows up when your mom dies matters more than the one who posts the best birthday tribute. Why the person who asks how you actually are, then waits through the pause while you decide whether to tell the truth, is doing attachment repair work whether they know it or not.

Gay men can learn new patterns. We’re not doomed to recreate childhood wounds forever. But it requires naming them first. Seeing them clearly. Refusing to call survival strategies “personality” anymore.

The transformation happens when we stop treating our need for genuine connection as the problem and start seeing the culture that taught us to hide it as the actual issue.

What Your Body Already Knows

Notice what happens in your chest when you see your friend group making plans without you. That drop. That specifically hollow feeling like your sternum forgot how to be solid.

That’s not paranoia. That’s your attachment system sending accurate data about provisional belonging.

Your body knows the difference between being included and being tolerated. Between friendship and social performance management. Between people who know you and people who know your highlight reel.

The question isn’t whether you can trust your gut. It’s whether you’re ready to listen to what it’s been trying to tell you about which relationships feel safe and which ones keep you in constant audition mode.

Therapy spaces exist for untangling this. For learning to tell the difference between old wounds and present danger. For building new patterns with people who can handle your whole self, tears and snot included.

Not fixing. Seeing. That’s what changes things.

Some mornings I still think about that voice note. The specific courage it takes to admit, even to yourself, that your friends might not know you at all.

Maybe that’s where it starts. With one person brave enough to stop performing long enough to notice how exhausting the show has become.

Then finding just one other person willing to do the same.

If you enjoyed this post, please tap the Like button below. ❤️ It really does help.

This Substack is for educational and informational purposes only. It does not replace therapy, diagnose, treat, or prevent any mental health condition.

Client and personal examples may have been altered to safeguard privacy and maintain confidentiality.

The depth of sadness I feel about this is hard to express.

I don’t think I ever looked deep enough at why, as a gay man, I felt repelled by the gay male community. As someone on the HSP spectrum, I recognized it on other levels and knew that I could not live in that community.

I don’t think the name of your newsletter has ever felt more appropriate.

I learned to find empathy, depth and genuine friendship outside the gay community (which I think is a bit of an optimistic misnomer anyway). The friends I'm closest to, who've been my friends for decades, through good times and bad, are heterosexual women. Now in my sixth decade and happily married to a man, I can count on the fingers of one hand how many gay male friends I have.